All Saints Kingston has a rich and varied history. Before All Saints Church Church was built, its site was an important estate of the West Saxon Kings and host to several Saxon Royal coronations.

All Saints Kingston has a rich and varied history. Before All Saints Church Church was built, its site was an important estate of the West Saxon Kings and host to several Saxon Royal coronations.

All Saints Kingston is the ancient church of Kingston parish that, at one time stretched from Molesey to Richmond. Kingston was a Royal estate, and King Egbert of Wessex (grandfather of Alfred the Great) held a Great Council here in 838AD and is understood to have built a church dedicated to All Hallows, i.e. All Saints, on the site.

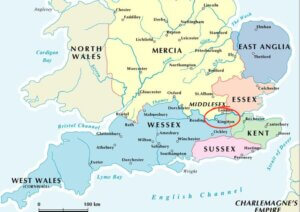

In the tenth century Anglo Saxon period, Kingston was a place of significant historic importance with seven Saxon kings (including the first ‘Kings of England’) traditionally thought to have been crowned here; Edward the Elder, reign 899-924 (son of Alfred the Great), Athelstan, reign 924-940 (first King of what we now call England), Edmund, reign 939-946, Eadred, reign 946-955, Eadwig (sometimes called Edwy) reign 955-959, Edward the Martyr, reign 975-978 and Ethelred the Unready (meaning ill advised) reign 978-1016. The Saxon King Egbert held his Great Council of 838 AD ‘in that famous place called Cyningestun’ and over the following centuries as many as eight Saxon kings were consecrated here. The most well-known of these Saxon kings was Athelstan, the first ruler who could truly be considered the King of England. After being crowned in Kingston in 925 AD Athelstan defeated the Scots and Vikings, unifying regional kingdoms into one nation.

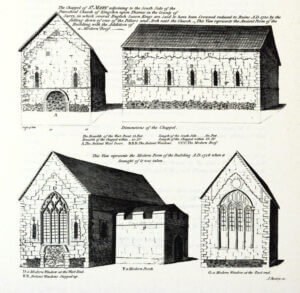

Stones and brass plates mark the site of the St Mary’s chapel just outside the south door (towards the marketplace) which was probably built before the 1066 Norman conquest and which stood until the 18th century. When the current building was built in the 12th century, it was linked to the chapel via an opening from the transept which then served as a Lady Chapel to the “new” larger church, however, the chapel collapsed in 1730 when the Sexton was digging a grave near it. Little remains except a few stone fragments and parts of the east window of the area known as the Vicar’s Burial Place.

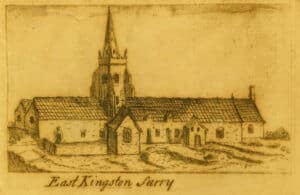

The current buildings tower originally had a wooden spire, but this was destroyed by lightning in 1445 and was not rebuilt for 60 years. In 1703, the spire and the tower down to the belfry windows were damaged in a storm. Five years later the tower was rebuilt in brick, but without the spire. In 1973 it was strengthened internally, its surface brickwork and the stonework of the windows renewed and the bells re-hung.

All Saints has witnessed Kingston’s transformation from a small scattered settlement into the bustling, lively town it is today. Click here for a short history guide.

For a short history leaflet of the church, please click here.

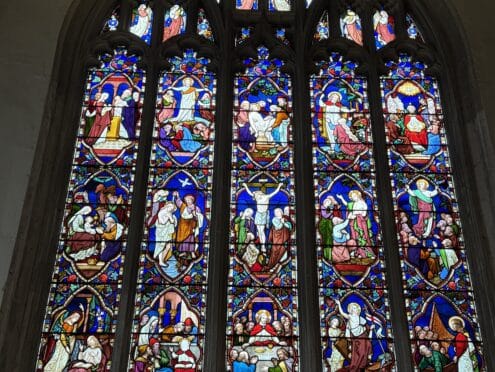

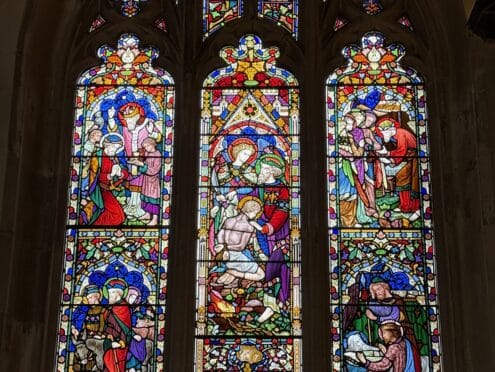

Stained Glass

All Saints has many stained glass windows, mostly depicting bible stories but also some memorials and a set which tell some of the church’s oldest stories. All Saints’ windows are not as old as you might think, and most of the glass you see can now is Victorian. All Saints may well have had stained glass in some of its windows in the Middle Ages, but none of this has survived. Some may have been deliberately destroyed in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and other glass simply replaced with plain glass as it suffered damage or when the stonework of the windows needed repair.

Visitors to All Saints can follow a free self-guided trail of the church’s most interesting stained glass.

In the north aisle, to the west of the organ, two windows tell some of All Saints’ oldest stories despite being some of our newest glass, dedicated in 1956 and made by Lowndes and Drury of Fulham. Window 14 shows the arms of Saxon king Edward the Elder, son of Alfred the Great, and suspected to have been crowned at Kingston. This is accompanied by the arms of Merton Abbey, Patrons of the living from All Saints’ construction to the abbey’s suppression in 1538, and of King’s College, Cambridge and its founder King Henry VI. The college bought the gift of the living in 1786. Window 15 contains pieces of ancient glass from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

The windows are by several of the leading firms of the period and are outstanding examples of High Victorian Gothic Revival. The earliest is the east window in the south choir aisle (2), by Ward & Nixon and probably from 1852. The great east window (1) is of 1860 by the same firm, now Ward & Hughes, and it was followed by windows by William Wailes (3), and Lavers and Barraud (4, 5, 11, 13, 19) all designed by Nathaniel Westlake; 12 probably designed by Milner Allen; 21-2 in the clerestory) of whom Nathanael Lavers was a member of the congregation. The great west window (12) is a particularly fine example of rich colouring and the figures of the Apostles with obviously Victorian heads are probably portraits of local people. Apart from no. 11 these all date from the 1860s. The windows of the south transept and the south wall of the nave (6-9) date from the period of Pearson’s restoration in the 1880s and are by Burlison & Grylls, who were also responsible for no. 10, in 1920. These have lighter colouring and were influenced by late fifteenth century Flemish and German glass. With one exception the other windows are all of the twentieth century: nos18 and 19 in the Holy Trinity chapel by Christopher Webb and the heraldic window by Lowndes & Drury. The sole exception is the fifteenth and sixteenth century glass from the Thomas and Drake collection installed in 1956. The windows were given as memorials, mainly to local people but in some cases to members of the East Surrey Regiment.

Download Guide to Our Windows

Windows Gallery

Echoes of Slavery booklet

All Saints Church and Contested Heritage

The community of All Saints Kingston deeply regrets the part that slavery has played in the history of our nation. We recognise that some of the memorials in our historic building are connected to those who were associated with slavery. We want to remember the past honestly and published this booklet to signal a positive and constructive response to the Church of England’s call to affirmative action on any instances of contested heritage that the church building may contain. We have also adopted the anti racism charter.

This booklet was authored by John Dewhurst with Pippa Joiner and David Robinson to whom we give thanks.

Hard copies are available near the welcome desk.

Download the Echoes of Slavery Booklet

Monuments

All Saints contains hundreds of memorials spanning seven centuries. The memorials tell the human story of the church and the lives of those important in its history. There are memorials to families, benefactors, civic leaders and captains of industry. There are also many memorials to military men and church personnel. Visitors to All Saints can follow a free self-guided trail of the church’s most interesting memorials.

Image of Louisa Theodosia – One of our most beautiful memorials is our statue of Louisa Theodosia, Countess of Liverpool, sculpted by Sir Francis Chantrey. A fine example of Chantrey’s portrait sculpture, it has been exhibited at the Royal Academy (1824), the National Portait Gallery (1981) and the Mappin Art Gallery (1981). Born in 1767, Louisa was 28 when she married Lord Liverpool, Prime Minister 1812-1827. They lived at Coombe House in New Malden, where Louisa died following a long illness in 1821.

Image of Davidson family – These monuments are the work of Charles Regnart and John Ternouth, two distinguished sculptors. The memorial is dedicated to the Davidson family – Henry and Duncan Davidson, and Duncan’s wife, son and daughter-in-law. The Clan Davidson were from Tulloch in Scotland and were wealthy enough to own property in Scotland, Jamaica, South America and London. Although several members of the family were buried at All Saints no links to Kingston have yet been found!

Sir Anthony Benn– The tomb of Sir Anthony Benn (1570-1618), Recorder of Kingston and London, shows Benn in his lawyer’s robes. He and his wife, Jane Evelyn, lived in Norbiton Hall, Kingston. Benn was ‘Recorder’ at Kingston and later in London, an important legal position judging civil cases.

Philip Medows – This monument is by John Flaxman who was the first Professor of Sculpture at the Royal Academy (in 1810), and arguably the most important English sculptor of the period. The monument is dedicated to Sir Philip Medows (1717-1781), deputy ranger of Richmond Park and husband of Lady Frances Pierrepont, daughter of the Earl of Kingston upon Hull.

Cesar Picton – This modest memorial pays tribute to Cesar Picton who died in 1836. Cesar was six years old when he was brought from Senegal to Kingston as a servant to Sir John Philipps of Norbiton Place. Cesar was left £100 by Lady Philipps when she died, and he used the money to establish a coal merchant’s business in Kingston. By the time of his death Cesar was a wealthy man, both because of his successful business and money left to him in the wills of all three Philipps daughters.

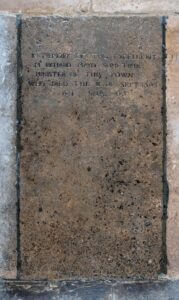

Staunton children – This monument pays tribute to ten of Edmund Staunton’s children. Edmund Staunton was Rector at Kingston from 1633 – 1658, and was a prominent churchman who had influence with the Parliamentarians during the Civil War. The memorial records the tragic deaths of ten of his children, all during childhood. Edmund died at the age of 71 and was buried in Hertfordshire.

The Moorman Altar Cloth

Theo Moorman (1907–1990) , studied at Central School of Art from 1925–28, balancing gallery exhibitions with an extensive range of commissions for altar cloths and hangings for churches, including the remarkable Zimbabwe altar cloth (measuring 3.3 square metres) for All Saints Church, Kingston-upon-Thames, commissioned by Brigadier Rushmore, a member of the congregation as a symbol of hope for racial harmony.

The commission was in response to the murder of Brigadier Rushmore’s sister-in-law by nationalist freedom fighters in what is now Zimbabwe, being determined that good should come out of their family tragedy.

The artist, who was ‘particularly proud’ of the work, devised a brilliant abstract design in striking green, red, blue and yellow tones based on the theme of light.

The work, finally dedicated in 1981, reveals her innovative inlay technique. This technique, which still bears her name, involves two warps, one to create the ground and a tie-down warp, which allows the weaving of inlaid front-face weft threads to form the pattern. Following an extensive professional restoration in 2014, the church still uses the cloth today.

This is an extract from an article written by Amanda Game, commissioned by the Decorative Arts Society entitled ‘Oxford Gallery and Innovative Art Textiles 1968-1980 ‘, published in Decorative Arts Society Journal 49 (2025), pp. 106-125, and reproduced here courtesy of the author and the Decorative Arts Society.

https://www.decorativeartssociety.org.uk/journal/

Christus Sculpture

A striking sculpture, ‘Christus’ by Peter Eugene Ball is on permanent display near the North door.

We are grateful to Jim and Eppie Bates who gifted this beautiful sculpture to us, for public viewing. The artwork was dedicated at our Christ the King Service on November 26th 2023, with a grand unveiling at our Epiphany Carol Service on January 7th 2024

Poppy Cascades

Seeing a photo of the poppy cascade made for Remembrance Day 2024 by St Paul’s Church Hook, we were inspired to plan a similar one for this year, the 80th anniversary of the end of World War 2. We started by visiting St Paul’s where they kindly showed us their method and we tried to estimate how many poppies it would take to make one cascade for our space – about 700 we thought. Could we manage to get so many? We set up a display in the Church cafe area appealing for poppies, reached out to our contacts and waited, with some anxiety. We chose not to specify the method, size or shade of red; we wanted a variety of poppies because those we planned to commemorate were people of every race, creed and class. We counted the poppies as they came in and gave a sigh of relief when we reached 700 – then when we reached 1,000 we wondered if we would have enough for a second cascade. Our final total was over 3,000, so we have been able to make 3 magnificent cascades plus a carpet of poppies round the baptismal font.

Our poppies are, as we hoped, very varied: some sewn, some knitted, some crocheted and of different sizes and shades of red – who knew there were so many reds? Among the reds came in the occasional purple for the animals sacrificed to war. So many local people and various organisations have contributed poppies, most notably RBKares the Refugee Sewing Group who made 1,000, so the displays truly represent the diversity of present day Kingston. We thank all those who joined with us to create them and special thanks must go to Liz Deller who masterminded the construction of the cascades.

All Saints Church is proud to commemorate in this way all who have lost their lives in the many wars that still afflict our planet. The displays will stay in position until November 26th, after which we get the church ready for Advent, the season of pre paration for Christmas, when by tradition churches are bare so the festive season when it comes will be all the more joyous for the contrast. We hope that the many people who pass through our building while the poppies are displayed will be moved by them to pray, in their own way, for peace in God’s world.

Egbert’s Great Council

Kingston’s royal connections are first evident in the record of King Egbert’s Great Council in 838, which was held here. It is recorded as happening ‘in that famous place called Cyningestun’, the name denoting a royal estate, probably including a consecrated building, and suggesting that this was a ‘well-known’ place. The Council was attended by the King, his noblemen, the Archbishop Ceolnoth of Canterbury and other senior clergymen. At the meeting, the church and King formed a strong bond and allegiance with each agreeing to help the other. The archbishop probably anointed Egbert’s son Ethelwulf as the next king following Egbert.

At this time Kingston was a small group of scattered settlements. Although All Saints had not yet been built, the community was likely served by a wooden minster church.

Documents from the time describe the council as taking place at ‘illa famosa loco quae appeletur Cyningestun in regionnae sudregiae.’ This means that it was ‘that famous place called Cyningestun in the region of Surrey.’ The name suggests a royal estate, including a timber hall and a church, which would probably have sat on the current site of All Saints.

Crowning Saxon Kings

More than 1000 years ago, Kingston was the place where England began. It has traditionally been claimed that seven Saxon kings were crowned on the site of All Saints, and we have good historic evidence that at least three were, with Edward the Elder beginning the tradition.

List of Kings

- Edward the Elder (899-924) Son of Alfred the Great, brother of Athelflaed, “Lady of the Mercians”

- Athelstan, first King of England (925-930)

- Edmund (939-946)

- Edred (946-955)

- Edwy (955-959)

- Edgar “the Peaceable” (959-975) Although there is not enough evidence to say so with certainty

- Edward “the Martyr” (975-978)

- Ethelred “the Unready” (978-1016)

The Saxon cross fragment housed in All Saints formed part of a larger cross possibly erected to commemorate one of these coronations. The coronation stone which is still on display in Kingston is said to have been the stone which the kings sat upon whilst they were crowned.

King Athelstan

In AD 924, Athelstan (sometimes spelled Aethelstan) became the King of Mercia and Wessex, joining those areas to form the kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons.

In 925 he was crowned with great ceremony in Kingston. Athelstan first greeted his people in the marketplace before entering a church, which was probably wooden and stood on the site of our present All Saints Kingston. Athelstan was the first King to be ordained with a crown placed on his head, rather than a helmet and a replica of this crown is in the glass case by the West door. His coronation laid out the responsibilities the king and his people had to each other, forming the foundation of our modern coronation service. The Christian hymn Te Deum and the coronation ‘ordo’ were both compiled for Athelstan and used for all subsequent coronations through to the coronation of our Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 and King Charles III in 2022.

Seven Saxon Kings are understood to have been crowned at Kingston (although evidence is argued by historians), with Athelstan considered the most important. Building on the work of his grandfather Alfred the Great, he united the separate regional kingdoms into one nation, becoming the first actual King of England through battle and quashing multiple rebellions and invasions.

As King of the English from 927, he was the first English king to conquer northern Britain. Athelstan was a particularly successful soldier and defeated a combined army of Scots and Vikings at the battle of Brunanburh in 937. He even stamped his coins and charters with ‘Rex Totius Britanniae’ asserting himslef as the ‘King of Britons’

Athelstan was son of Edward the Elder and his first wife Ecgwynn and partially raised by his powerful aunt, Aethelflaed, lady of the Mercians. Athelstan had no children and was succeeded by his half brother Edmund (son of Edward the Elder and his third wife Eadgifu). He had a half sister; Eadgyth, through his father’s second marriage and her remains were found in the twenty first century in Germany. The bones are the oldest found of a member of English royalty and it is amazing to think that she may have attended her brother’s coronation here in Kingston more than a millenia ago in 925. Read about this story by clicking here.

David Woodman book on Athelstan

The Seven Saxon Kings Embroidery Project

For full details of the Seven Saxon Kings Embroidery Project, please click here or go to main menu on the welcome page and choose the “Seven Saxon Kings” page.

Our aim is to make the “Kingston tapestries” as synonymous with the first kings of England as the Bayeux tapestry is with William the conqueror and the battle of Hastings. Six of the Kings are now complete and in situ in the East end of the church, near our award winning Cafe, and looking glorious! The remaining embroidery of Ethelred the Unready is currently being embroidered by the artist and should be ready in 2026.

We will shortly move to phase 2 of the project with our plans for full interpretation and education on the panels.

For an early article on the project, please click here. For a PDF booklet outlining the project and early visualisation of completed images please click here.

Can you help us ensure Kingston’s Saxon heritage story is enjoyed by future generations for many years to come? To donate to the project, please click here

The Book of Names Appeal

In order to raise much needed funds for the project, we established the Book of Names appeal. Donors of £100 or more were invited to have a name of their choice embroidered into the book, created by Jacky Puzey. The appeal was a huge success, enabling the project to move ahead to seek additional funding. We would like to thank each and every donor and hope that you will enjoy seeing your chosen name displayed.

The book is now complete and we are awaiting the display case to house it next to the embroideries. If you wish to view the book before the display case arrives, please email [email protected] so that we may arrange an appointment.

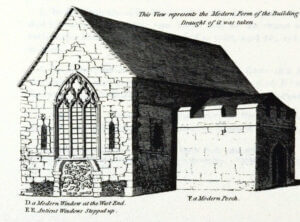

St Mary’s Chapel

St Mary’s was built in the eleventh century 1030-1050, probably before or shortly after the conquest of 1066 and pre-dated the building of All Saints by at least fifty years.

When All Saints was built in the twelfth century, St Mary’s stood to the south side of the church. The south transept of All Saints was later extended to join the north wall of St Mary’s, linking the two, with St Mary’s becoming an annex known as the Lady Chapel.

By the late seventeenth century visitors to St Mary’s recorded that inside the chapel there were paintings of the Saxon kings rumoured to have been crowned here, with captions explaining that fact. However, shortly after the chapel was redundant and was being used as a timber store for All Saints.

The building collapsed in 1730. The building’s foundations had been weakened by Sexton Abram Hammerton’s grave digging. When the building collapsed the Sexton, his son and his daughter Hester had been nearby digging graves and so were trapped in the rubble. The Sexton died in the accident, but miraculously Hester and her brother were pulled from the rubble alive after seven hours. Hester had helped her father dig graves since she was 13 years old so took over his job and was a well-known person in Kingston.

The site of St Mary’s was excavated in 1926 by William Finny, antiquarian and mayor of Kingston. His archaeological digging revealed that St Mary’s Chapel had measured 60 feet by 25 feet and had flint foundations. Floor tiles found dated to 1050 earliest, and many to the thirteenth century, which shows that the chapel was being maintained and repaired. Finny believed that St Mary’s was built next to the ruins of an old Saxon church on All Saints’ site, perhaps destroyed by Viking raids in the eleventh century. You can still see where St Mary’s stood in All Saints churchyard, to the south of the church, where plaques at St Marys’ four corners were laid in 1936.

1120 – All Saints Church built

All Saints Church was built in the twelfth century, possibly by Gilbert the Norman, Sheriff of Surrey, under the orders of King Henry I. The date of the building is disputed. We think that the 1120s/1130s is a safe assumption but there is some evidence that points to a date later in the twelfth century.

All Saints was cruciform in shape, with a nave the same length as the present one, but probably without aisles, and with a central tower. The south transept was later extended to join the north wall of St Mary’s, which became the Lady Chapel for the church.

Medieval All Saints

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries Kingston grew prosperous on the wool trade and the population grew. As Kingston became larger and wealthier the church was enlarged to accommodate the larger congregations and provide more altars for the saying of Mass and statues and pictures for private devotion.

The central tower was rebuilt in the early 14th century and by the end of the Middle Ages it had a wooden spire. In 1370 the Bishop of Winchester ordered that the chancel roof of All Saints Church must be repaired. The chancel may have been widened in the late fourteenth century and the whole building was enlarged in about 1400, when side aisles were added on either side of the nave and the nave itself was probably widened. The wall painting of St Blaise which was painted in the church in the fourteenth century speaks of the importance of the wool trade in Kingston.

Towards the end of the fifteenth century the chancel was enlarged to its present size. A chantry chapel was founded by William Skerne in the south chancel aisle and the Holy Trinity chapel (now the East Surrey Memorial Chapel) was founded on the north side.

1459 – St Mary’s Chantry

St Mary’s Chantry was founded in 1459 on the south side of the chancel by William Skerne to pray for his family. Chantry chapels were founded and endowed by rich parishioners who would pay for a priest to say prayers for their family members and assist their souls’ journey to heaven.

William Skerne founded St Mary’s Chantry to pray for his uncle and aunt. His uncle, Robert Skerne of Down Hall, Kingston, had died in 1437. He had been a well-known and respected local lawyer. Robert’s wife Joanna Skerne was the illegitimate daughter of Edward III and his mistress Alice Perrers. Memorial brasses to the couple can still be seen in the church.

1477 – Holy Trinity Chapel

Groups of less wealthy locals could form groups to jointly endow a chantry chapel to pray for the souls of its members. The Holy Trinity Chapel was built on the north side of the chancel in 1477 by the Guild of the Holy Trinity, a religious society whose purpose was to promote worship. The Holy Trinity Chapel was later refurbished to serve as the East Surrey Regiment Memorial Chapel.

1503s – Churchwardens

By the sixteenth century the Priest of All Saints was assisted in managing his growing parish by two churchwardens. These were local men chosen each year by the parishioners and the priest.

Their duties were mostly financial and to do with the repair and maintenance of the church and its contents. For example, they were in charge of paying for repairs for the church organ and bells. Their accounts from the early sixteenth-century survive to this day.

Tudor All Saints

The churchwardens were responsible for the maintenance of the fabric and their account book beginning in 1503 shows us the range of work required on the building and its contents. The chancel, the preserve of the clergy, would have been divided from the nave, where the congregation gathered, by a rood screen showing Christ on the cross with the Virgin Mary and St John. The inside of All Saints would have been striking, with bright colours and rich furnishings. The church contained an impressive number of altars and priests to serve them; there were probably six priests at the start of the sixteenth century!

During the Reformation All Saints’ shrines and altars were dismantled and the rood screen was removed. Coloured glass, images, statues and wall paintings were removed, and pews were introduced for seating. All Saints’ interior was much more dull after the Reformation.

1530s – The Reformation at All Saints

The Reformation in the sixteenth century marked a turbulent period for All Saints Church. The ways people were allowed to worship changed, the church’s ornaments and vestments were confiscated, and the appearance of the church was drastically altered.

In 1549 the government demanded an inventory of goods of Kingston church, and in 1553 most of Kingston’s church goods were confiscated. The altar became a ‘communion table’. The rood screen separating the altar from the congregation was taken down and sold. Many images and statues would have been removed.

1633 – Edmund Staunton

In 1633, Edmund Staunton became vicar of Kingston. Staunton was an energetic ‘Puritan’ minister. He was typical of the increasing popularity of preachers who attacked the Church of England during the reign of Charles I (1625-49).

1654 – Richard Mayo

‘The excellent Mr Richard Mayo’ was a Presbyterian minister, probably resident in Kingston from 1654 and minister at All Saints from 1656 until 1662.

Richard Mayo was removed as vicar, after the Restoration of Charles II (1660) because he refused to take the Anglican sacraments and pledge allegiance to the King. He and many of his supporters formed a separate congregation which met at various places in Kingston.

Stuart / Georgian All Saints

In 1703 the church spire topped with a weathercock, which was the pride of local townspeople, was destroyed in a storm. The tower was so badly damaged it had to be dismantled. It was rebuilt in brick in 1708, but the spire was not replaced.

Inside, the aisles were rebuilt in brick in the 1720s, and given plaster ceilings. Fashionable pedimented doorways in the classical style were later built at the west end (where the old Norman doorway was bricked up) and at the entrance to the north transept. High box pews and galleries were introduced during the 17th and 18th centuries. There was a gallery at the west end, two on the south side of the church, while another over the north aisle was added in 1793. The galleries provided extra seating to cope with Kingston’s growing population.

1703 – The spire comes down during the great storm

During a great storm in 1703 the spire collapsed and the tower also had to be dismantled because it was also badly damaged. It was rebuilt in brick in 1708. The spire, however, was not replaced, significantly changing the look of the church from outside.

1730 – Collapse of St Mary’s Chapel

In 1730 St Mary’s Chapel, an annex to All Saints which had stood for 600 years, suddenly collapsed. The building’s foundations had been weakened by Sexton Abram Hammerton’s grave digging. When the building collapsed the Sexton, his son and his daughter Hester had been nearby digging graves and so were trapped in the rubble.

The Sexton died in the accident, but miraculously Hester and her brother were pulled from the rubble alive after seven hours. Hester had helped her father dig graves since she was 13 years old so took over his job and was a well-known person in Kingston.

1817 – Samuel Gandy

Kingston’s vicar from 1817 to 1851 was the ‘eccentric but genial’ Samuel Whitlocke Gandy, a popular and committed clergyman. He penned the lyrics of a number of hymns, including ‘What though th’accuser roar’:

What though th’ accuser roarOf ills that I have done!I know them well, and thousands more:Jehovah findeth none.

He increased the seating at All Saints by enlarging the around the nave, but by 1830 the church was full to capacity (again) and Gandy founded new churches. The first was St John the Divine, Richmond (Kingston parish covered Richmond until 1849), and then in other outlying parts of the parish at Ham (1832), Hook (1838) and Kingston Vale (1839), and then in the expanding suburb of Norbiton (1842). Another new church was founded by the developers of the Surbiton estate (1845).

Victorian All Saints

All Saints was heavily restored by the Victorians. The first major phase, under the architect Raphael Brandon took place in the 1860s. His work included removing the west gallery (the old organ gallery) and the creation of the great west window, containing stained glass by Lavers and Barraud. The ceilings were also reconstructed. An original Norman west door was uncovered during restorations, but unfortunately it was decided that the doorway was too old to survive, and it was photographed and destroyed.

The second phase of restoration was undertaken by John Loughborough Pearson in the 1880s. Pearson enlarged the two transepts, removed the remaining galleries and gave new roofs to the nave, transepts and aisles. The height of the east and west pillars under the tower was raised, and most of our current stained glass is from this period in the second half of the nineteenth century.

In 1793 The Ambulator, a guidebook to London, was reporting that it was the stone on which the Saxon kings sat while being crowned. The stone is Sarsen which is a type of silcrete rock found scattered naturally across southern England and famous for being used to build Stonehenge.

In 1793 The Ambulator, a guidebook to London, was reporting that it was the stone on which the Saxon kings sat while being crowned. The stone is Sarsen which is a type of silcrete rock found scattered naturally across southern England and famous for being used to build Stonehenge.

Our Sarsen stone may have been recovered from the ruins of St Mary’s Chapel built approx 1030. William Finny, antiquarian and mayor of Kingston conducted an archaeological dig of that site in 1926, concluding that it was built next to the ruins of an even older Saxon church (which our current All Saints now stands on), which could point to our Sarsen stone coming from that earlier building, putting it in the time frame to have been used in Saxon coronations. It is a tenuous link that the Coronation Stone is the block on which the Saxon Kings sat during the ceremony of the coronation, but an enjoyable addition to the story.

In 1850 it was properly displayed in the marketplace, on a plinth carved with the names and coins of the seven Saxon kings crowned upon it, and surrounded with ornamental railings in a ‘Saxon’ design. In 1935 the monument was moved outside the town’s Guildhall and has been visited by various dignitaries and modern royalty.

1862 – 66 – Brandon’s restorations

The first major phase of Victorian restoration of All Saints took place in the 1860s under the architect Raphael Brandon. His work included removing the west gallery and the creation of the great west window, the stained glass being by the firm of Lavers and Barraud. Unfortunately, when the Norman west door was uncovered, it was judged incapable of being preserved, and it was photographed and destroyed.

1884 – 88 – Pearson’s restorations

The second phase of restoration was undertaken by John Loughborough Pearson in the 1880s. This included inserting new tracery in windows which had been altered in post-medieval times, extending the transepts, constructing new roofs, removing galleries and heightening the east and west arches of the tower.

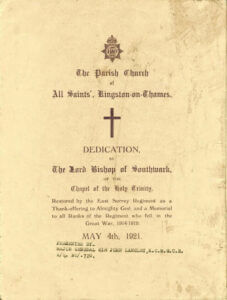

East Surrey Memorial Chapel

East Surrey Memorial Chapel

After the First World War the Holy Trinity Chapel was restored to become the Memorial Chapel of the East Surrey Regiment, and pay tribute to Kingstonians who had died fighting in the war. Restorations were carried out by friends, relatives and comrades of the regiment. They were completed in 1921 and the chapel was dedicated as the Regimental War Memorial by the Bishop of Southwark.

A book of remembrance listing the names of the regiment’s 6000 men and officers who had died in the war was placed in the Chapel. The colours of the East Surrey Regiment were hung in the chapel. The regiment also erected a memorial gate on the entrance from the market place to the church. It was dedicated by the Bishop of Kingston on Armistice Day in 1924.

In 1921 the Chapel of Holy Trinity was dedicated as the Regimental War Memorial of the East Surrey Regiment. The Regiment had long enjoyed close connections with Kingston, and the Chapel was refurbished to pay tribute to its men who had died in the First World War.

The East Surrey Regiment’s connection with Kingston dates back to 1782 when county titles were introduced for Regiments of Infantry. The 70th Regiment became the 70th Surrey Regiment and a Depot was established in Kingston to recruit local men. The barracks on Kings Road, Kingston were designed by the Royal Engineers and completed in 1875. In 1881 the 31st and 70th Regiments combined and became the East Surrey Regiment with the new barracks as their Depot. Around 84,000 men passed through the Depot and were trained there during the First World War, between 1914 and 1917.

Work on restoring the Chapel of Holy Trinity started in 1920 and was undertaken by friends and family of the Regiment. The Chapel was reopened and dedicated by the Bishop of Southwark in 1921, and on Armistice Day 1924 the Memorial Gates at the approach to the church from the market place were dedicated by the Bishop of Kingston.

The Queen’s Royal Surrey Regimental Association continues its links with the Memorial Chapel at All Saints. Over the years it has made grants for refurbishments and improvements, and the Association still attends the annual Remembrance Day service as well as civic occasions in the Borough.

Today the Chapel is used as a place for prayer and contemplation. It contains Books of Remembrance, or ‘of Life’, containing the names of those killed in twentieth century conflict. It was made and bound by the Hon. Norah Hewitt in memory of her brother, Captain the Hon. A R Hewitt DSO, who lost his life at Ypres on 25th April 1915. It was enlarged to record the names of the members of the Regiment who lost their lives in 1939-45. The names of those who have died since 1945 are recorded in an additional book on the south side of the Chapel.

The oak panels on the walls are memorials to officers who served in the East Surrey Regiment. There is a section on the North Wall commemorating those who hold the Victoria Cross. The Sanctuary Lamp was presented in 1913 by the Major and Mrs J L Congdon, and burns in perpetual remembrance of those who died in 1914-18.

There are two memorial windows of stained glass in the north wall. One is dedicated to the memory of Major General Sir John Longley KCMG, CB, Colonel, The East Surrey Regiment from 1920-39 and his son Charles Raynsford Longley. Charles was killed at the Battle of Jutland in 1916, and the window was dedicated forty years later in January 1956. The second window is dedicated to the memory of Col H H W Pearse DSO.

To find out more about the Queens Royal Surrey Regiments please visit www.queensroyalsurreys.org.uk

One handsome brass plaque mounted on the wall of the South Aisle in the East Surrey Memorial Chapel commemorates Lieutenant Francis Edward Blackwood. During lockdown 2020 John Dewhurst, former churchwarden of All Saints, has undertaken fascinating research and has written a book which explores the story of Blackwood and life in the Edwardian Army, the training (or lack of it) and social privilege. Please click for more information on the book This Brave Young Officer.

1978 – 79 – Cawdron’s reordering

The church was reordered in 1978-9 by architect Hugh Cawdron. It was transformed from its Victorian appearance to provide a more flexible space not only for worship but for musical and dramatic performances. The pews were replaced with flexible seating, and a square altar was installed beneath the central tower. The choir stalls were moved from under the tower to the first bay of the Nave, and they are now in the Abbey at Milton Abbas. The church was then able to serve a small congregation in the east end or a larger one in the nave.

Twentieth century All Saints

After the refurbishment of the East Surrey Memorial Chapel in the 1920s, the church underwent little renovation until the late twentieth century. In 1978-9 the church was reordered by the architect Hugh Cawdron. The High Altar was placed beneath the tower with new choir stalls in the eastern bay of the nave. The Victorian pews were replaced by chairs. These changes reflected new approaches to worship and also the need for flexibility when the church was used for concerts and other events.

Modern-day All Saints

Modern-day All Saints

The interior of the church as we now see it is largely the result of a further reordering, combined with redecoration, by architect Ptolemy Dean in 2013-4.

This was intended to enhance its beauty and its ability to meet new needs. A new entrance was created on the north side of the church, opening All Saints up to the main commercial centre of the town.

A new entrance was created on the north side of the church, opening up All Saints to the main commercial centre of the town, this necessitated some internal reordering, relocating the altar into a more or less central position in the nave of the church. The east end has been opened up to serve as a flexible area for worship and community use including an amazing cafe and children’s area and the niche’s which were formerly behind the alter are now the setting for an amazing set of intricate contemporary embroideries featuring each of the Seven Saxon kings believed to have been crowned here.

All Saints’ musical traditions

All Saints has a strong musical tradition going back hundreds of years. By the sixteenth century All Saints had a choir which walked in ceremonial processions and sang at special services. The ‘quyer’ at this time was probably made up of priests who participated in chanting and plainsong, perhaps with ‘fabardon’ harmonisation. There was an organ in the church by 1509 at the latest which was used to accompany plainsong at the main Sunday mass. By 1527 there were apparently two organs in the church.

After the reformation, from 1570, there is no reference to the organ in the churchwardens’ accounts for more than 200 years. There is also no specific evidence of a choir from the 1580s. Music in All Saints was probably restricted to the congregational singing of metrical psalms, led by the parish clerk. By the eighteenth century these were probably supplemented by hymns, which were permitted to be sung before and after the service. The clock in the tower was fitted with a carillon which played the tunes ‘Hanover’ (O Worship the King) and ‘Easter Hymn’ (Jesus Christ is Risen Today).

A new organ was installed in the west gallery in 1793, paid for by the parishioners. The organist employed was Mary Varden, a local girl from a musical family notable for her young age of 13. She was employed as organist for 40 years until her death. Organists continued to be appointed as necessary, with Louisa Varden (Mary’s sister) succeeding her in 1833. They were generally selected by competition, and were always local women, until Elizabeth Kensett (organist from 1849) was replaced. After Elizabeth, only men were appointed to the role of organist. This is part of wider trend across England, fuelled by the growth of a profitable music ‘profession’. Some said that larger, modern organs were too physically challenging for women to play.

There was a choir of children and adults by 1817 at the latest, and probably considerably earlier. A new organ by Willis was installed in 1867, although almost immediately a new vicar reduced the scope of the music and the choirmen decamped to Hampton Court chapel. In 1877 the musical tradition was restored. From 1893 to 1954 Percy Alderson and then his son Philip, who are commemorated in the south porch, were successive organists. In the past half century the range and quality of music has continued to develop. In 1958 an organ by Comptons replaced the much-altered Willis organ.

Over the past half-century the range and quality of music has continued to grow, and in 1988 an organ by the distinguished Danish builder Erik Frobenius was installed, securing All Saints as Kingston’s leading venue for concerts as well as other dramatic and artistic events.

The choir continues and is known nationally for the quality of its music making and sings an extensive repertoire. As well as contributing to the worship of the church, it makes broadcasts and recordings, has excellent connections with local schools and has regularly produced choral scholars at Oxford and Cambridge Universities.

To learn more about the choir, please click here or find the page via our main menu.

The Frobenius Organ in All Saints

All Saints possesses a fine three manual, 39 speaking stop Frobenius organ, built in 1988. Key action is mechanical and stop action electric. It was originally placed centrally in the north aisle but during the recent refurbishment it was moved further east, thus enabling a better balance with the choir. At the same time it underwent a thorough cleaning and upgrade of the operating systems. There are now 999 channels of general pistons with stepper and 25 channels of divisionals. This work was undertaken by Mander Organs, who now maintain and tune the instrument.

It is a versatile instrument, able to cope with most periods of the repertoire in recital as well as fulfilling its vital roles of accompanying the choir and leading the congregation.

Click here for the Organ stoplist

Architecture

All Saints Church looked very different from All Saints today when it was first built. The church was cruciform with a tower at its centre. To the north of the tower was the chancel, and to the south there were two transepts of roughly equal depth to the present aisles.

Nearly 900 years old later little if any of the original fabric of the building remains. During nineteenth century restorations an original Norman west door was uncovered, but was judged incapable of being preserved and unfortunately destroyed.

All that remains of the twelfth-century church in the present fabric are stones where the westernmost nave pillar in the south arcade meets the west wall. It is probable that these stones formed part of the wall of the Norman nave. These are shaped with an axe and not a chisel, an implement which came into use later. The core of the tower, now masked by later work, also dates from this time, and other features which were re-used by later builders are now on display.

Visitors to All Saints can follow a free self-guided trail of the church’s most interesting architectural features and learn more about the history of the building.